piñon

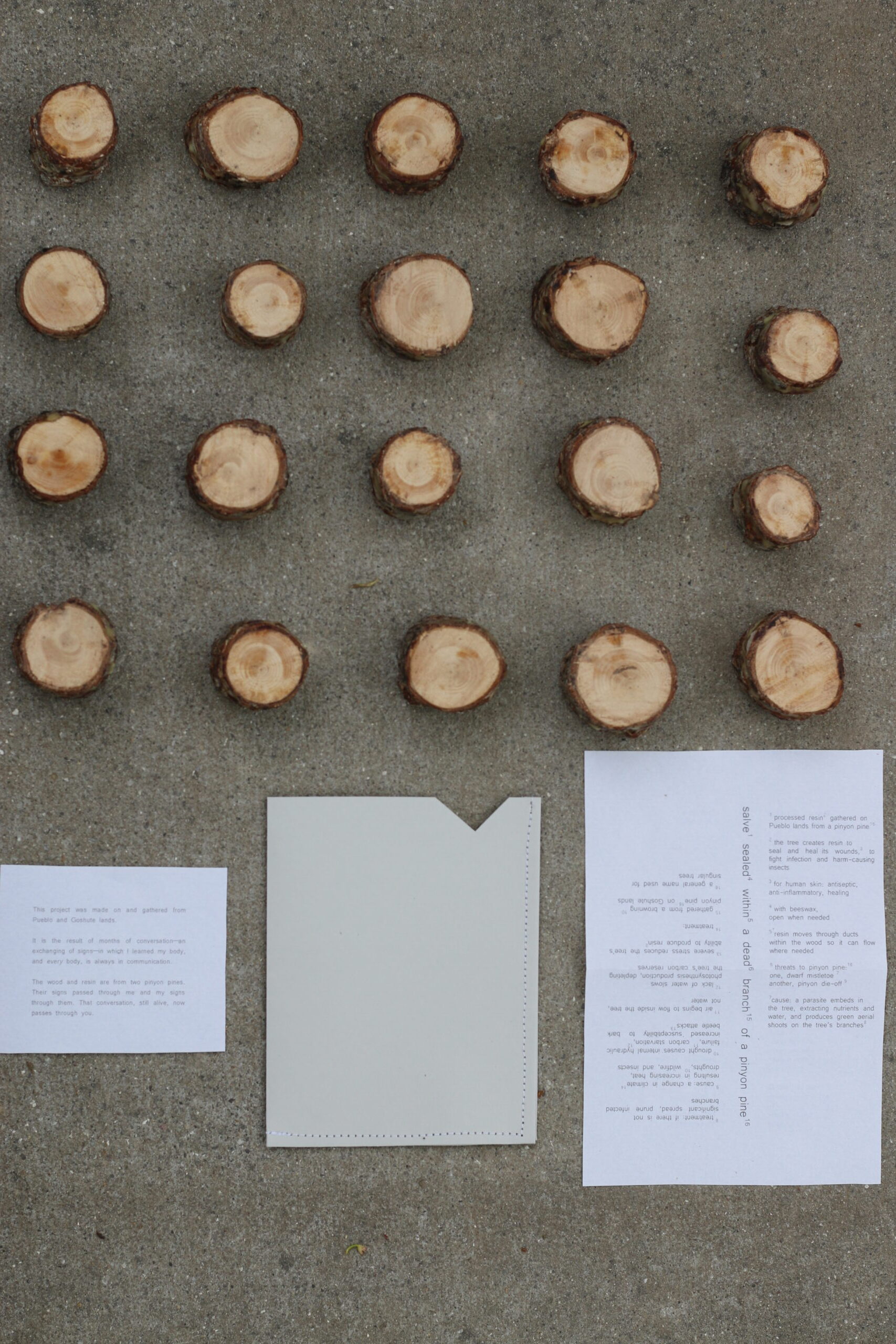

salve, made form piñon resin, sealed with beeswax in piñon branch, with sewn envelope and printed paper

(printed text at the bottom of the page)

About the project:

“All life is semiotic.” —Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think

When I read that, it changed me.

The book carrying that sentence declared that “we humans…are not the only ones who interpret the world.” It said that “signs are more than things. They….are ongoing relational processes.” It said that everything from the audible voice of an animal to the body of a plant—with its adaptations representing its environment—is a sign. Thus “landscape should be considered a giant network of signals and signs.”

For me, such ideas have profound implications on how to include the more-than-human in the sign-making tradition called “art.” It asks, How do you make signs about someone who can make their own signs?

It’s a question that questions the colonial relation between the human and more-than-human. In colonial thought the world is “compartmentalized” with these divisions creating hierarchies, and those hierarchies perpetuating “the inferiority of some and the superiority of others” (Frantz Fanon & Richard Philcox). In other words, it creates subject-object relations, where the (human) subject “stands as the crux of being, power, and knowledge,” while the (more-than-human) object is to be observed and documented (Nelson Maldonado-Torres). In art, this framework leads to extractive representation—where the more-than-human is reduced to metaphor or object and used by an artist for their own gain.

I’ve thought a lot about this framework, in my worry of slipping into it. I have problematized such relationships in other work, showing what felt wrong. Yet I have wondered, What would right feel like?

This question came with me, as I spent a day among sandstone mountains. I walked by a piñon pine, who stood on the lip of the summit, open to the harsh high wind. All over the tree’s bark was cracked and separated. Resin colored the seams. I stayed with the pine, listening to the story coming through signs. I knew that piñons produce resin to heal wounds and defend against harm—and here was so much of it. It littered the soil below. I knew of resin’s medicinal properties, not only for the skin of a pine, but also the skin of a human.

Indigenous elders taught me about gathering from another being. They taught me to ask permission, including stating the purpose of your gathering, which instantly checks any motivation. So I asked, stated, and listened, then gathered from the resin lying on the soil.

Days passed. I had yet to process the resin. Yet my mind kept returning to the tree. I had listened and asked, but the thought kept coming: You took more than you gave. So I read all I could about piñon pines—from their resin production to the current threats they face. I returned to the summit, finding the exact tree, swollen with wounds, and I asked a different question. Then I saw what I’d read: dwarf mistletoe. The parasite was already seeding on

the tree’s branches, meaning it had been present inside for a while. I left, knowing only the removal of infected branches would stop the spread, and I returned, saw in hand.

On that summit I felt how acknowledging another as an equally-capable subject and listening to their signs combine and coalesce into relation—where signs direct relation, and relation directs signs. It’s a relation that can become reciprocal. A relation that can become beautiful.

This was during the first months of a pandemic—a pandemic brought on by the ever-increasing press of the human on the more-than-human. Terms like shelter-in-place and lockdown were still frighteningly new. Fear was draining store shelves and immense uncertainty filled minds. I thought of the pine’s response to harm or loss: make something that heals, not just yours, but other skin.

So I made the resin into a salve and wrote the story of who it came from. I placed the salve in the branch of a piñon pine, which I gathered from a pine who died by drought. (Drought, brought on by climate disruption, is one of the other threats to piñon pines.) I made dozens of packages, which friends from New York to California opened to be met with the smell of piñon pine—that deep sweet aroma, of its own sign.